Qui est donc ce personnage dont certains cconnaissent la galerie photographique, située rue Didouche Mourad, en plein coeur de la capitale, où seuls osent s’aventurer les habitués ? Dans ce local sombre et mystérieux, Abdeslam a transporté un peu de son désert natal :Du 11 janvier au 10 février 2012

altAbdeslam KHELIL, artiste photographe algérien, saharien, est né le 15 mars 1942 à Ouargla (à 800 km au sud d’Alger).

Qui est donc ce personnage dont certains connaissent la galerie photographique, située rue Didouche Mourad, en plein coeur de la capitale, où seuls osent s’aventurer les habitués ?

Dans ce local sombre et mystérieux, Abdeslam a transporté un peu de son désert natal : du sable répandu sur le sol derrière la baie vitrée, des plantes sèches « pour l’accompagner », le bureau tendu de peau de chameau qu’il a confectionné de ses propres mains, le tapis coloré, cadeau de ses amis Touareg, recouvrant la banquette de la pièce, des meubles tapissés de liège (son oeuvre également), et la moquette couleur de Sahara.

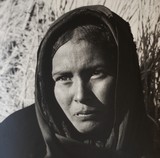

Dans cette atmosphère qui enchante le visiteur, l’envoûte même, on se laisse bercer par Les quatre saisons de Vivaldi, la IXème symphoniede Beethoven... «Je ne comprends pas que l’on puisse avoir de la haine après avoir écouté cela » dit-il... et on peut se recueillir devant de somptueux tableaux photographiques. Les siens. Ceux de Khelil. Tous en noir et blanc.

Des paysages et des portraits, du Sud algérien le plus souvent, sa source, sa ressource, son origine, son bonheur. Abdeslam est un artiste qui vit à la frontière entre deux mondes, à la lisière entre le rationnel et l’irrationnel. Il est autodidacte. Il a commencé à côtoyer la photographie à l’âge de dix ans.

A l’époque, il travaillait comme apprenti dans l’atelier photographique de son frère aîné, à Ouargla. « Je lui apportais des seaux d’eau tirée du puits pour le développement des photos. »Souvenir qu’il évoque avec naturel, lui, le benjamin d’une fratrie de quatre frères, et pourqui l’obéissance et le respect à l’égard des aînés est une valeur fondamentale. A dix-huit ans, Abdeslam s’envole pour Paris. Il y suit un stage de deux ans chez Kodak. Aujourd’hui, le regard dans le vague, un sourire lumineux aux lèvres, il cite l’avenue Montaigne, le quartier de Montmartre et tant de lieux gravés dans sa mémoire. Au début des années soixante, il s’installe à Alger.

Mais l’homme est nomade et il revendique ses origines. En effet, durant des années, il sillonne l’Algérie, le Sud notamment, le Tassili, s’arrête à Djanet, pousse jusqu’aux frontières maliennes et mauritaniennes, séjournant souvent chez ses amis Touareg, sa famille adoptive. Il réalise, chaque fois, de merveilleux clichés. Cet amoureux du désert affirme tranquillement : « Au Sahara, les gens n’ont rien à prouver, ils savent ce qu’ils sont".

Un jour, j’y retournerai, même si je dois habiter une cabane de paille ; j’y serai heureux, je regarderai la lune et les étoiles, oeuvres de Dieu, loin dumonde, des agressions de la ville, près de lanature, et je retrouverai mon palmier et mon âne, content de recevoir une carotte. La richesseest un état d’âme. L’homme est un perpétuel insatisfait et je refuse d’être esclave de la bêtise sociale.» Pour Khelil, la réussite n’a rien à voir avec la réussite matérielle. Il a d’ailleurs été dans une réelle aisance financière, jusqu’à ce que le terrorisme des années quatre-vingt dix « chasse [son] public occidental », qui composait l’essentiel de sa clientèle. Depuis, il s’est enfermé dans sa bulle d’artiste, imperméable aux banalités de la vie, fidèle à sa galerie, ses génies, ses djnoun: Vivaldi, Mozart, son sable, ses plantes et ses photos.

Fidèle, également, à cette bougie qu’il allume chaque matin en hommage à une personne, un événement, à Dieu tout simplement, ou à la vie. «La Vie n’est pas du domaine du pouvoir humain. Je n’aime pas voler ou faucher Dieu, je veux accomplir mon noble devoir d’humain. Ses clichés ont traversé les mers, ont circulé de par le monde, l’homme est apprécié, très souvent admiré. Son oeuvre fait incontestablement partie de ces merveilles du patrimoine culturel algérien, tellement négligé cependant, si peu valorisé. En exposant un échantillon de son magnifique travail (« La femme à la mouche », « L ’enfant et l’infini », « L es pieds », « L es épis », « Les Touareg », « La mosquée de G hardaïa »,...) moi, Rym KHELIL , sa fille, je veux aujourd’hui rendre hommage à cet immense artiste.

VERNISSAGE: MERCREDI 11 JANVIER 2012 A 18H30

The modern, main boulevard bordering the bay in Algiers housed lots of boutiques and other shops, and had a very French feeling—more like Nice than anything I’d seen so far in Africa. My traveling companion at the time, Lynn, and I strolled along the boulevard and came upon a photographer’s gallery displaying interesting photos of Tuareg men and women in its window. I was captivated, both by the harshness of the life the photos conveyed and by their artfulness.

We went in, looked around at the very impressive photos, and took in the calm atmosphere of the gallery. We were about to leave when the gallery clerk told us there was also an exhibit downstairs. She suggested we see it, showed us the stairs, and down we went. On first sight, it was as if we’d been transported to a desert oasis. All four walls were covered, floor to ceiling, with huge photos of a palmerie, much like the one we’d seen a week earlier at Tinerhir in Morocco. Not only were the walls covered with the palmerie, but the floor was covered with sand, the ceiling with date palm fronds, and a fallen palm tree lay at one end of the room. I was entranced with the whole scene and stood on the stairs, staring, but Lynn decided to walk around. Suddenly she let out a scream. I thought she’d seen a desert rat or something, but no; on the ground, hidden from view behind the fallen palm tree, was a man, sleeping. He woke at the sound of her voice.

We apologized for interrupting his nap, but he seemed not at all to be disturbed. We soon learned that he was the photographer, Khelil, a beautiful man, more black than Arab, about 30 years old, who’d learned photography in Paris at Kodak, then opened his gallery in Algiers about six years before. Ouargla, his hometown, where he took most of his photos, was in the desert. We chatted with him for a half hour or so, learning about his life, his work, his love for photography and for the desert. I was captivated by both his creativity and his emotional depth. I left his shop wistfully, feeling there was much more I’d like to have learned about him. But all I could do was to buy some of his gorgeous photos of Tuareg women and stroll further down the boulevard. From time to time we’d go back to his gallery and chat with him for a few minutes. I never really had a fuller conversation with him, but was always wanting one; the occasion just never presented itself.

A week later, we started off on a bus for the desert. We stopped in Laghouat and Ghardaia, both interesting towns, and then moved on to Ouargla. Once we arrived, we found a hotel, walked around a bit, then entered a café. Sitting at the bar, I looked over to a wall, where a large photo was hanging by Khelil, the photographer we’d met in Algiers. Happy to see the familiar picture, I uttered in French, “Oh, I know the photographer of that photo!”

The fellow tending bar said in French also, “Oh, you do? Well, he’s here.”

I thought he meant he was “from” here, which I knew; I replied, “Yes, I know, but he’s in Algiers now.”

But the bartender insisted, no, he was in town, as he’d seen him that morning. Soon another customer in the café, a man from the Syndicat d’Initiative Tourist Bureau, took us to the store where Khelil’s brother worked. We didn’t find his brother until later that afternoon. We told him we’d met Khelil in Algiers, and hoped to see him again. Khelil was out in the desert, taking more photographs, he told us. Could his brother ask him to come to our hotel if he was free that evening? Yes, if he returned in time. I didn’t really believe he’d come.

That afternoon we also met an Englishman, a geophysicist, who invited us to dinner in the evening. We told him we’d hoped to see Khelil later that evening, but we’d be happy to have dinner with him. During dinner, in came Khelil, like an old friend, and invited us to his house for tea after dinner. We readily accepted and after thanking the Englishman for dinner, went over to Khelil’s house, met his brother and sister, and had the conversation I’d been hoping to have in Algiers. Khelil was such a beautiful person, with a warmth and love for humanity which showed immediately in all his photos as well as in his person. After a few hours of conversation we said goodbye, knowing we’d probably never see each other again. He was heading north to Algiers and we were going south, farther into the desert.

It was another experience of serendipity—how things work out in a very surprising but natural way. I imagined that Khelil would remain as much a memory of Algeria as any of the other people we met there.

Blair Pamela - Psychologue (rétiréeº - Berkeley, Etats-Unis

14/03/2018 - 373094

-

Votre commentaire

Votre commentaire s'affichera sur cette page après validation par l'administrateur.

Ceci n'est en aucun cas un formulaire à l'adresse du sujet évoqué,

mais juste un espace d'opinion et d'échange d'idées dans le respect.

Posté Le : 10/01/2012

Posté par : dzphoto

Ecrit par : Par Rym Khelil

Source : http://www.cca-paris.com/